Author

Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) is the largest federal program providing cash payments and health coverage to insured workers with disabilities. To qualify for and retain SSDI benefits, applicants must have a medically determinable impairment and earn below a specified level of income.

The fact a person receives SSDI benefits does not mean they have no earning capacity. There are several reasons why the calculation of post-injury earning capacity in personal injury cases may differ from Social Security’s disability determination. Six of the biggest reasons are discussed below.

1. Conditions considered for SSDI determination may pre-date the event that is the subject of litigation.

While SSDI benefits may be awarded post injury, they may be based on a prior medical condition or set of medical conditions. The SSDI determination process considers all impairments an applicant claims, which may include chronic and degenerative conditions in addition to the alleged injury.

An SSDI application typically takes six to twelve months or longer to process and begin payments, if an award is made. The date of disability onset can be many years before the date of SSDI application, although back income benefits are limited to a twelve-month lump sum payment. Obtaining the established disability onset date for an SSDI beneficiary is important in litigation cases.

2. Workers may earn below full capacity to qualify for or retain SSDI benefits.

Because eligibility for SSDI benefits requires both a medical condition and low income, there is an incentive for applicants and beneficiaries to limit earnings to qualify for or retain benefits. Many economic studies have measured this disincentive, estimating that up to 50 percent of SSDI recipients would return to work in the absence of benefits.[1]

SSDI discourages work and earning at full capacity in two ways, through a substitution effect and an income effect:

- When a worker qualifies medically for SSDI but earns a little too much, working essentially becomes more costly and there is a financial incentive to earn less—this is the substitution effect.

- When a worker qualifies medically and prefers leisure to labor, given the value of SSDI benefits, there is an early retirement incentive to earn less and leave the labor force—this is the income effect.

Results from programs intended to promote return to work demonstrate that the income effect dominates for most beneficiaries.[2] This seems plausible when considering the most common SSDI recipient, an older male with a high school education (or less) with physical pain. Personal injury litigation and the value of potential settlements further increase the income effect and the disincentive to work.

3. The process for determining loss of earning capacity differs from the process for determining SSDI disability.

“Earning capacity” is defined as the expected earnings of a worker who makes choices to maximize what they expect to earn. The process for calculating economic damages due to a loss of earning capacity involves estimating the difference in the pre-injury and post-injury earning capacities, adjusted to their discounted present value. Determining post-injury earning capacity involves assessing what jobs the person can perform, what accommodations they may need, whether they will benefit from additional training or education, the availability of specific jobs in the area, and the expected wage. An individual’s medical condition and their return-to-work options are considered jointly when determining post-injury earning capacity.

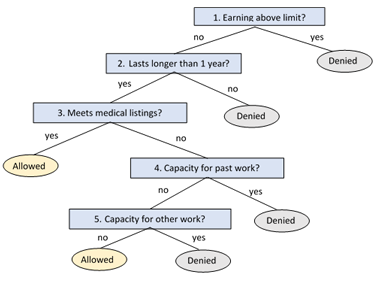

In comparison, SSDI eligibility is determined by a five-step sequential decision process:

- A worker’s income is evaluated. If monthly earnings are over a specified limit,[3] the worker is denied, without consideration of medical impairment.

- If the impairment is expected to last less than twelve months, the application is denied.

- The impairment is compared to the current SSDI medical listings, which include fourteen categories of mental and physical disorders. Standards established for allowance of these conditions have changed over the life of the program and are influenced by congressional legislation and political climates. If the impairment is listed, the worker is allowed benefits.

- Applicants with an unlisted medical condition are evaluated to determine whether they can do the work they did previously. The demands of their recent past work are considered along with an assessment of their remaining ability.

- If the worker cannot work in any of their past jobs, their capacity for any other type of work is considered. Step 5 relies on the Medical-Vocational Grids, rules that strongly favor applicants over age 50 for eligibility.

The SSDI disability determination process is summarized below.

Since post-injury earning capacity is evaluated jointly using medical assessment and ability to work, the outcome for a listed injury may differ from SSDI’s sequential evaluation. For example, suppose a worker with a musculoskeletal injury qualifies at the medical listing stage at step 3 and is determined eligible for SSDI benefits. Their capacity for past work at step 4 and capacity for other work at step 5 are not considered. Given this same worker and musculoskeletal injury in litigation, there may be no post-injury loss of earning capacity when the medical history, capacity for past or other work, and expected length of recovery are considered together.

4. SSDI continuing reviews are lagging and typically backlogged.

Beneficiaries are reviewed for continuance of benefits every three to seven years or more, depending on the expected duration of the beneficiary’s impairment and the availability of federal funds. Continuing Disability Reviews (CDRs) are typically backlogged for many years, because beneficiary rolls have grown and funding fluctuates with the political climate. Fewer than 10 percent of SSDI disabled workers are reviewed each year. A beneficiary who could medically return to work but limits earnings may receive SSDI benefits for several years before having a full medical review. Beneficiaries whose payments are terminated based on a CDR can appeal the decision. After appeals, final medical cessations occur in fewer than 2 percent of annual reviews. [4] This means only 0.2 percent of SSDI disabled workers are terminated through the CDR process each year.

5. SSDI disability determinations and reviews do not consider possible accommodations or innovations in assistive technology.

Vocational outcomes for people with disabilities have improved significantly due to advances in medicine and improvements in assistive technologies. However, since 1984 the number of SSDI beneficiaries per capita has tripled. One reason is the SSDI determination process does not consider these improvements when making disability determinations. The CDR questionnaire mailed to beneficiaries under review asks these questions:

- Within the last two years, have you worked for someone or been self-employed? (If yes, report dates worked and earnings.)

- Check the box which best describes your health within the last two years: (Better, Same, Worse)

- Within the last two years, has your doctor told you that you can return to work?

- Within the last two years, have you attended any school or work training program(s)?

- Would you be interested in receiving rehabilitation or other services that could help you get back to work?

- Within the last two years, have you been hospitalized or had any surgery? (If yes, report reason and date.)

- Within the last two years, have you gone to a doctor or clinic for your condition? (If yes, report reason and date.)

Missing from this questionnaire is any information regarding ability to work while being treated. It fails to identify workers whose ability to work improves due to treatment, assistive technology, or accommodations. Beneficiaries who may be able to work but have not informed their doctors are also not identified.

6. SSDI relies on outdated and oversimplified vocational evaluations.

In determining capacity for past jobs or other work, SSDI uses the Dictionary of Occupational Titles, first developed in 1938 and last updated in 1991. Outdated information on work available in the economy leads to incorrect and even biased determinations, as technology and job tasks have evolved considerably in the last four decades. The Social Security Administration recognizes this information is outdated and unreliable for disability determinations. It is developing a new occupation information system but has not yet implemented it.[5]

The last step of the determination process relies on SSDI’s medical-vocational grids, which divide workers into categories based on age group, education level, and past skill level. There are only three classifications in each category. SSDI determination does not consider the possibility of additional training or education to increase the person’s work options.

In personal injury litigation, however, a vocational expert uses vocational tests and a transferable skills analysis to assess a worker’s current job options and potential for additional education and training to increase those options. Sometimes, the SSDI’s limited grid structure may deem a worker unable to work, although that person can work with additional education or training. The worker may be able to perform jobs that are not in the Dictionary of Occupational Titles or for which the physical demands have changed due to new technology.

In summary, eligibility for SSDI benefits is not definitive evidence a person has little or no earning capacity. Earning disincentives and additional medical conditions unrelated to litigation may lead to cases where an SSDI beneficiary may have no reduced earning capacity. Constraints and limitations in the determination and review process lead to SSDI eligibility and continuance for individuals capable of earning substantial incomes.

[1] Kajal Lahiri, Jae Song, Bernard Wixon, “A Model of Social Security Disability Insurance Using Matched SIPP/Administrative Data,” Journal of Econometrics 145, nos. 1–2 (2008): 4–20.

[2] David H. Autor and Mark G. Duggan, “Distinguishing Income from Substitution Effects in Disability Insurance,” American Economic Review 97, no. 2 (2007): 119–124.

[3] $1,310 for non-blind in 2021.

[4] Social Security Administration, “Annual Report on Medical Continuing Disability Reviews, Fiscal Year 2016,” September 30, 2020.

[5] Occupational Information System Project, Social Security Administration, https://www.ssa.gov/disabilityresearch/occupational_info_systems.html.